I’ve always had a soft spot for airplanes. When I was a kid, I spent countless hours glued to Microsoft Flight Simulator, trying to land at airports I could barely pronounce.

It’s one of those passions that never really leaves you. But these days, I don’t get many chances to indulge it professionally. So, it felt like a treat when a story about aviation economics crossed my desk.

The inspiration for this article came from a Financial Times interview with the CEO of Embraer, who claimed that at least one new aircraft manufacturer will eventually break the duopoly between Boeing and Airbus.

I found his comment fascinating, as Embraer’s CEO lived through the most recent attempt. He had a front-row seat to it, in fact.

Such a story belongs to Bombardier, the Canadian manufacturer that once dreamed of standing shoulder to shoulder with Boeing and Airbus.

Let’s see what they tried to do, and why it didn’t work.

Mapping the Skies of the Aircraft Industry

To understand Bombardier’s decision-making, we need to start with a quick overview of the aircraft industry.

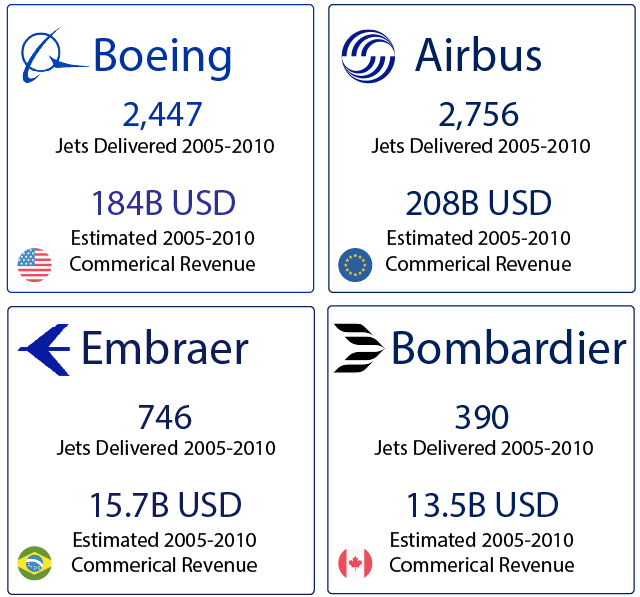

From about 1990 to 2020, the market was controlled by two duopolies:

· Boeing (U.S.) and Airbus (Europe/multi-country): the top end of the market, with aircraft of 100 seats and up, ranging from single-aisle to widebody.

· Bombardier (Canada) and Embraer (Brazil): the regional and business jet segment, with aircraft under 100 seats serving short routes.

There’s a silly economics joke that says: What’s worse than a monopoly? Two monopolies!

A monopoly has pricing power. They set price above marginal cost to get the kind of economic profits impossible in pure competition. This allows them to increase prices further and focus on keeping competitors out.

A duopoly, however, walks a tightrope, competing for market share while avoiding driving prices down. And because governments prohibit explicit collusion, the two players must “communicate implicitly” through market behaviour or informal networks.

Not exactly the best or the easiest approach. Nonetheless, both aircraft duopolies were successful worldwide for a long time.

Turbulence Ahead: The Challenges

To this day, the major airlines (Delta, American Airlines, United Airlines, etc.) fly fleets primarily composed of either Boeing or Airbus planes – while their exclusive regional airline partners fly Bombardier or Embraer regional jets. And breaking these duopolies are hard for any player because building aircraft isn’t like launching a new tech startup.

Three factors make this business uniquely complex:

1. Capital Intensive

Every stage of bringing a new aircraft to market—design, testing, manufacturing, and customer support—requires billions of dollars. There’s no quick or cheap way to prototype an airplane.

Manufacturers must build facilities, test engines, design systems, and meet strict safety and certification requirements. The amount of upfront capital required makes entry into the industry nearly impossible for small players.

2. Time Intensive

Even if the money is available, time is another massive hurdle. It typically takes around ten years from the moment engineers start designing a new airplane until the first one rolls off the production line and is delivered to an airline.

Because of these long cycles, any mistake or delay can cost billions and affect an entire generation of aircraft. It also means that by the time a plane enters service, market conditions or fuel prices might have changed completely.

3. Government Interference

Aircraft factories are major employers, offering thousands of jobs. For this reason, national and local governments often support them with subsidies, tax breaks, or direct investments.

But this political and economic importance creates complex dynamics. Governments want to protect jobs and domestic industries, which often leads to disputes, trade tensions, and political pressure.

After reading the above, you can tell why Bombardier’s dream of breaking Boeing/Airbus monopoly was so ambitious. But let’s see why they believed they had no option but to attempt it.

Climbing Too High: Bombardier’s Bold Lead

In the regional jets market, the carefully balanced duopoly also held for years. Bombardier and Embraer divided the sales, with customers choosing between them based on range, capacity, and price.

Bombardier held 60–70% of the market, but things began to shift as Embraer caught up and flipped that ratio.

The Canadian company revolutionized the regional jet industry in the early 1990s with its CRJ line. But Embraer soon followed with their E-Jet family, producing even more aircraft over time—roughly 1,700 compared to Bombardier’s 1,200 CRJs by the late 2010s.

Embraer’s aircraft were cheaper, slightly smaller, and more efficient for many regional routes. An advantage that mattered to cost-conscious airlines.

Bombardier’s leadership opted to make a bold move. They would break free from the regional jet market and compete directly with the big players. Their vehicle for doing so would be the new CSeries, a family of 100–200 seat aircraft aimed squarely at the Boeing 737 and Airbus A320.

It was an audacious decision. Boeing and Airbus planes have been the most-purchased commercial aircraft in history because of their versatility. They were available in many configurations, could fly over the ocean, and so on. Still, Bombardier’s executives believed they could carve out a niche.

And they had other reasons beyond ambition or Embraer’s competition at this stage:

· They were still facing post-terrorism (9/11) consequences.

· The 2008 financial crisis hit the aviation sector hard.

Passenger travel plummeted, aircraft orders slowed, and manufacturers were forced to scale back. Bombardier faced a difficult choice: either lay off thousands of skilled workers or find a way out.

Laying off engineers and machinists would mean losing hard-won institutional knowledge—people who knew how to design and build airplanes from scratch. And politically, large-scale job cuts in Quebec would have been toxic.

Bombardier pushed forward with the CSeries.

When Ambition Outran Altitude

When launched, Bombardier estimated the CSeries to cost around US$2 billion. By 2009, that ballooned to US$3.5 billion. In 2015, it reached US$5.5 billion—and would ultimately become US$7–8 billion.

Bombardier hadn’t launched a new aircraft in nearly two decades. Their internal capabilities had atrophied somewhat. Developing a clean-sheet design proved much harder than expected.

As overruns mounted, the company’s financial position worsened. In 2015, Bombardier sold 25% of the CSeries program to the Quebec government for US$1 billion. Two years later, the Canadian federal government injected another US$370 million.

The Delta Deal: A Discount Too Deep

Unfortunately, despite all the Canadian investment, sales weren’t happening. Air Canada, of course, put in some orders, and other small foreign orders came in. But that was about it.

Until 2016, when Bombardier finally got a major deal: Delta Air Lines placed an order for 125 CSeries aircraft.

It should have been a triumph. It was a good-sized order. But it triggered a chain reaction that ultimately destroyed Bombardier’s commercial jet ambitions.

· List price: around US$75 million.

· Sale price: roughly US$20 million.

In the airline industry, discounts of 50% from list are common due to the risk involved, so a sale price of US$37 million would be expected. But US$20 million apiece was astonishingly low, probably far below cost.

Bombardier was probably desperate to land a marquee customer. But Boeing didn’t like that discount at all.

Boeing’s Decline and Fury

When Bombardier introduced the CSeries, Boeing was already showing signs of weakness—declining competitiveness, production challenges, and growing anxiety about new competitors. The 737 MAX disasters, poor decisions, and lack of safety culture exposed how far they had drifted from their engineering roots.

For decades, Boeing and Airbus had been locked in a powerful duopoly. But by the mid-2010s, Airbus had taken a clear lead—especially in the single-aisle market with its A320 family, which was outselling Boeing’s 737 across the board.

Airbus’s efficiency and design updates made its planes more appealing to airlines, while Boeing was struggling to keep up.

Then came to the market Bombardier’s CSeries—a smaller, more efficient jet aimed right at Boeing’s core territory. When Delta ordered over 100 of these aircraft, Boeing suddenly faced a third competitor in its most profitable segment.

This alarmed Boeing also for a couple of other reasons:

1. Boeing’s business model relied heavily on economies of scale. They produced roughly 400–500 units of the 737 each year, spreading their fixed costs (factories, suppliers, labor) over a large number of planes.

If a new entrant like Bombardier captured even a small slice of that market, Boeing’s production could drop to 150–300 aircraft annually. That would leave the company with the same fixed costs, but far fewer planes to spread them across—a financial nightmare.

2. Adding to Boeing’s worries was Bombardier’s partnership with COMAC, the Chinese state-owned aircraft manufacturer. The two companies began collaborating on cockpit interfaces and electrical systems, helping each other cut costs.

For Bombardier, it was a way to access China’s massive and fast-growing aviation market. For COMAC, it was a chance to gain Western engineering expertise and credibility. For Boeing, it was another factor to worry about.

To stop the Delta/Bombardier deal, Boeing filed a formal complaint with the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) alleging illegal dumping.

From their perspective, Bombardier—heavily subsidized by the Canadian government—was dumping aircraft into the U.S. market below cost, undercutting fair competition. And in 2017, the ITC sided with Boeing, imposing a 300% tariff on CSeries imports.

For Bombardier, that was a death sentence. The U.S. is the world’s most important aviation market. With tariffs tripling the sale price, Bombardier’s only major order was suddenly unviable.

Airbus to the Rescue

Bombardier was out of options. They were drowning in debt, losing market share, facing incredible development costs.

Enter Airbus.

In 2018, Airbus struck a deal to acquire 50% of Bombardier’s CSeries program for one dollar.

Yes, one dollar.

The symbolic sale price reflected the reality that the program was effectively worthless to Bombardier. And to anyone else, in fact.

The Quebec government retained its 25% stake, and Bombardier kept the remaining 25%—for the moment. Airbus later bought that out too, for a modest US$591 million in 2020.

The CSeries was rebranded as the Airbus A220 and continues in production today in Alabama (U.S.). Still, it’s hard to tell why Airbus acquired the CSeries program. Indeed, they had already discussed a partnership or takeover of the CSeries back in 2015. But the A220 competes with the successful A320. And airlines prefer not to diversify their fleets because it simplifies maintenance, reduces pilot training demands, and streamlines their parts supply.

More likely, they saw an opportunity to keep Boeing from acquiring Bombardier’s assets and to expand their own presence in North America. There may also have been a political dimension to the move—an effort to curry favor with the Trump administration and avoid steep U.S. tariffs on Airbus products.

After the Fall: Bombardier’s Exit

Bombardier’s aviation empire collapsed. Their dream of competing with Boeing and Airbus was over.

They sold their Q400 turboprop line to De Havilland Canada, their CRJ regional jet business to Mitsubishi, and wound down what little remained of their commercial aircraft division.

Bombardier ended up back where it began: focused solely on business jets, the one division coming out relatively unscathed.

Pierre Beaudoin—the heir to the Bombardier family controlling nearly half of the company’s voting rights despite owning only 12% of the shares—lost his CEO position in 2017 after years of heavy losses and controversial compensation.

That left Embraer enjoying near-monopoly status in the regional jet market. And I believe they are going to continue as a standalone company unless they get a very good deal from Boeing or Airbus.

Indeed, Boeing tried to acquire 80% of Embraer in 2017—a defensive strategy to bundle smaller jets with larger ones and match Airbus’s expanded lineup. It would have been a smart horizontal acquisition, but COVID and trade disputes derailed the deal, leaving Boeing with a US$150 million bill for walking away.

Mitsubishi, mostly a supplier to Airbus and Boeing, was once considered a possible competitor. They put together a regional jet (MRJ90) and secured 200-300 orders. But they never delivered and seem to be staying out of the market for the moment.

Lessons for Managers

Now that you’ve read the full story, here are the lessons for every stakeholder in the aviation industry—and for any manager tempted by the allure of bold diversification.

Embraer: Stay focused on what works. The regional jet market is profitable and defensible. Entering head-to-head competition with Boeing and Airbus would be dangerous, especially without the backing of a major economy like the U.S. or China.

Boeing: Fix your manufacturing and culture before chasing new deals to avoid being overrun by Airbus. Quality will determine whether Boeing survives this era.

Airbus: You won this round. Ensure you keep the lead by watching Boeing’s next moves and remaining relevant to your customers. At the same time, maintain strategic goodwill with the U.S. government, which can be just as critical to success as product innovation.

Bombardier: If you’re working there, focus on making the business jet division shine. It’s the company’s last stronghold.

Airlines: Consider the geopolitical risks of your fleet choices while the United States is in a state of protectionism.

Final Thoughts

When Embraer’s CEO suggested that a third player could one day challenge Boeing and Airbus, I think he was right. But that challenger won’t come from Canada or Brazil.

Embraer would be making a mistake if they entered into competition with Airbus or Boeing. They’d face the same set of problems that Bombardier had. Embraer lacks robust government support backing their access to the U.S. market. Nor do they have a history of building large aircraft.

More likely, the biggest threat to Boeing and Airbus duopoly is the Chinese COMAC for the following reasons:

· Over time, the Chinese industry moved from basic assembly work to highly sophisticated production, supported by advanced supply chains and vast industrial clusters.

We’ve already seen this progression in other sectors—BYD, for example, evolved from producing batteries to becoming one of the world’s top electric vehicle makers, competing directly with Tesla.

· COMAC enjoys far stronger state backing than Bombardier ever did.

· Bombardier was largely confined to the North American market. COMAC, on the other hand, has broader opportunities across Asia, Africa, and emerging markets.

In short, COMAC’s strength lies not just in aircraft design, but in the ecosystem behind it: the manufacturing depth, the political will, and the global market access that give China a real shot at rewriting the balance of power in aviation.

Ultimately, the challenges of the aircraft industry are simply too large for most new entrants to overcome.

Breaking a duopoly requires more than innovation and ambition. In aviation, altitude is everything. And without the lift of political or industrial power, even the best designs can stall.